Dainu Raksti

or (The Symbols of Traditional Poetry)

by: Alma Ulmane

Description

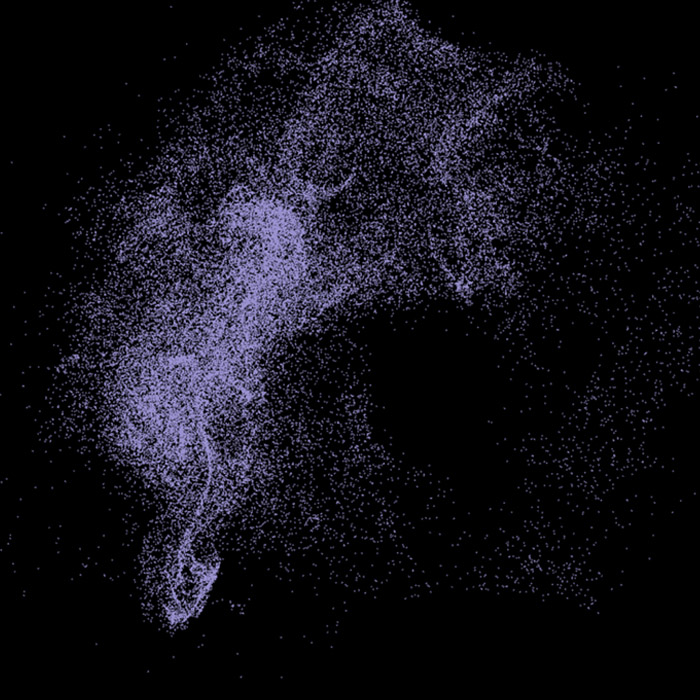

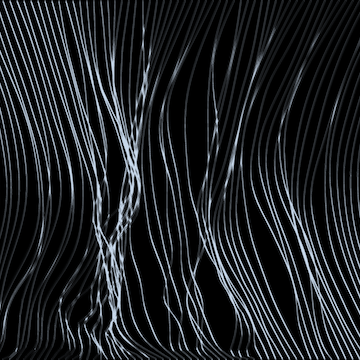

Dainu Raksti (The Symbols of Dainas) is a piece primarily exploring the artist's personal heritage. Combining various notations of language and algorithmic drawing it aims to reimagine dainas (traditional poetry) as computer generated images. The piece is a response to the debate that culture and tradition should be preserved through the creation of new and unique pieces rather than reproducing historical examples. This work is attempting to link traditions passed down through the generations with contemporary computational practices.

The original inspiration for the piece stems directly from textiles, however the piece has been produced with paper to reinforce the link with written language. Language has been transmitted in many ways throughout the centuries, including balls of wool with knots, all the way to strips of paper with morse code on it. Coincidentally the first computer programs were paper punch cards used by Ada Lovelace in Jacquard weaving.

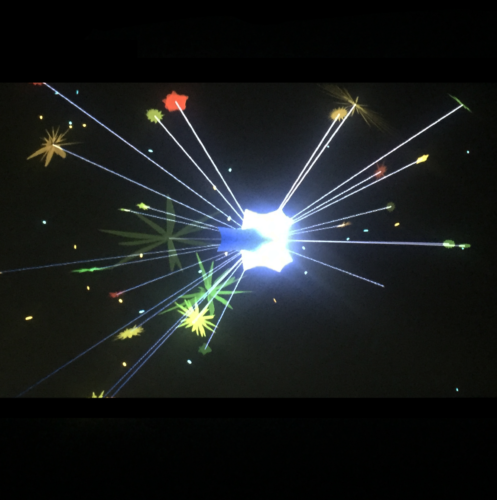

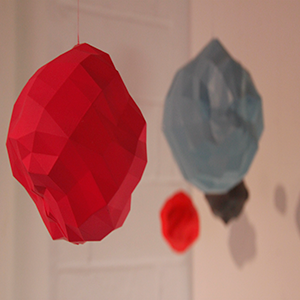

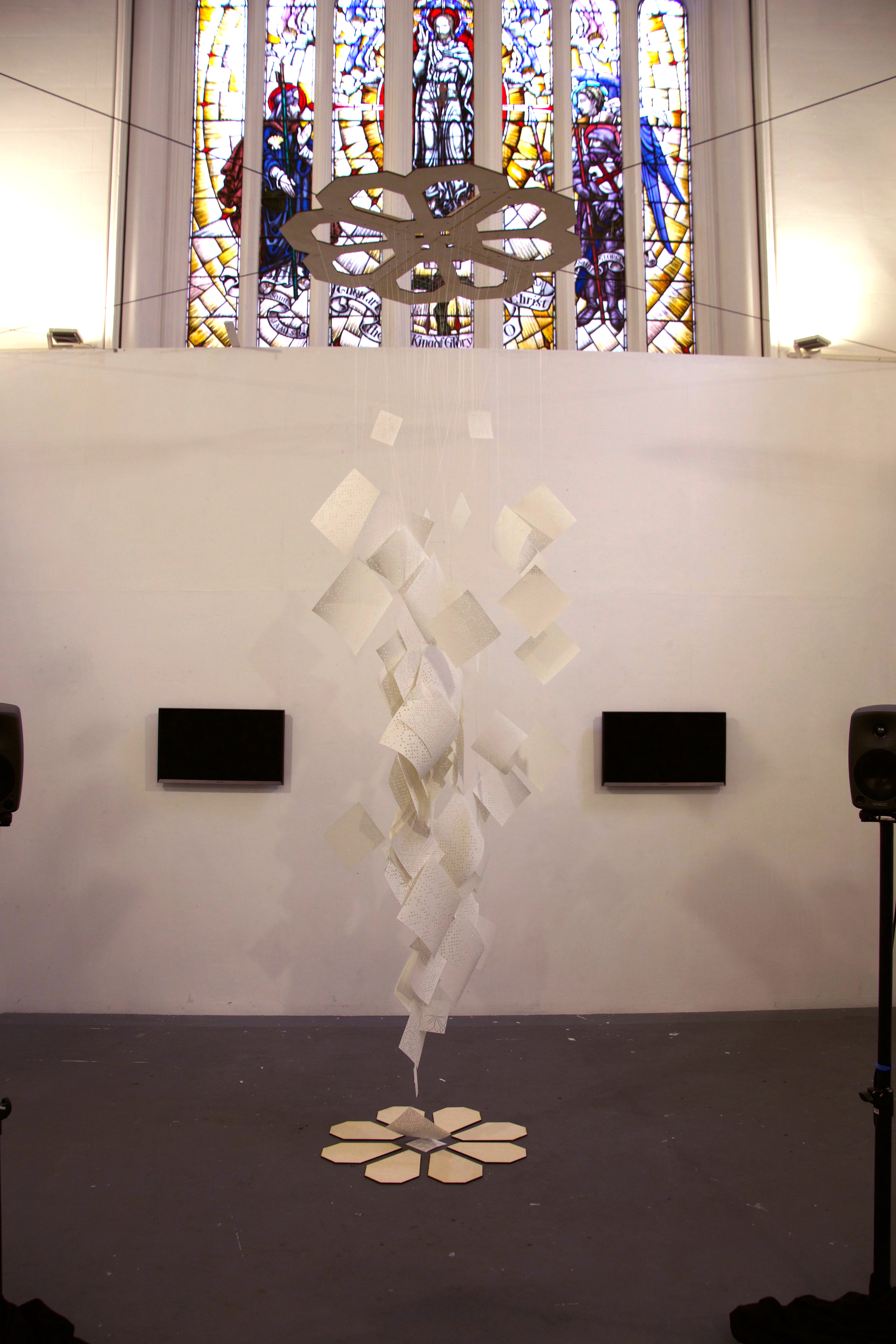

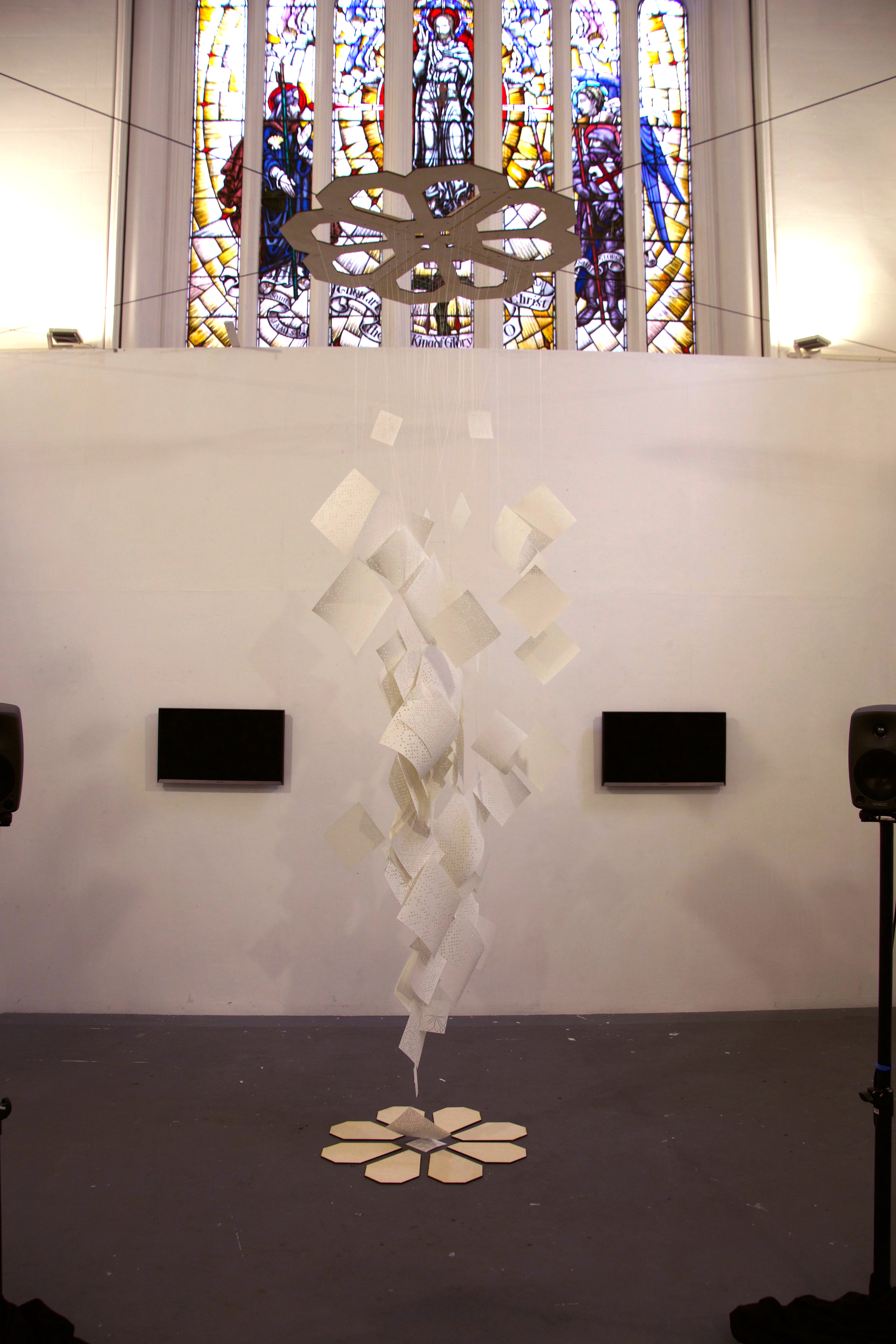

The finished piece is an installation of many dainas, transliterated into image format, floating in the air from a sun symbol frame.

Audience

The piece is primarily intended for a Latvian audience with, at least, a rudimentary understanding of the significance of both the dainas and the patterns used in Latvian culture. As the celebrations for the centenary are fast approaching, more and more artists in Latvia are creating works to celebrate their heritage and the occasion. As such the intended audience would not need complex explanations into the topics the piece is exploring.

As the piece was displayed at Goldsmiths, with a primarily non-Latvian audience, a consideration was connecting with the audience, without having to give them a history lesson. This was intended to be done through a video where various Latvians explained what dainas and the symbols are and how they view them in today's context. Sadly due to time constraints and a corrupted SD card the video didn’t go up with the piece.

The video I created instead showed the “transliterated” images of the dainas interspersed with the actual dainas with an English translation. What I didn’t realise at the time I was making this, is that it wouldn’t be enough for people to make a link between the image and the translated poem. One of the reasons behind this decision was the fact that most of the dainas are written in archaic Latvian using words not commonly found in English or in some cases untranslatable. Translating all the dainas “transliterated” to an image into English is not something that was possible within the timeframe.

The translations of the dainas to English caused problems in itself. Most of the dainas hide the true meaning in subtext, based on assumptions that the reader will know enough about Latvian culture, history and everyday life. For example:

Aiz ko man brāļi pirka Why did my brothers buy me

Vizuļotu vainadziņu? A tinsel wreath?

Druvâ man saule lēca, In the fields the Sun rises for me,

Druvâ saule norieteja. In the evenings it sets.

The daina is about a young girl not wanting to get married, preferring the freedom of staying with her family. In Latvian culture a wreath (whether it is of flowers, tinsel or other materials) represents virginity. Yet without this particular knowledge, a non- Latvian audience is simply unable to fully understand the particular daina. From the few members of the audience with the required background knowledge that I spoke to, my intent came across and the idea behind the work was understood. However, more could have been done to fully engage with the rest of the audience by making both the culture and the exact nature of the translation more transparent.

Creative Research

The work done in my second year at Goldsmiths - my triptych of tapestries [1] reaffirmed my love for working with my heritage. It is a subject I seem to be more interested in the more I know about it. Whether it is my cultural heritage such as stories and myths, textiles and ceramics, symbols and poetry or personal heritage such as my family traditions and ancestors, the subject has always appealed to me. I knew very early on therefore that I wanted to work with heritage; something very inherently my own.

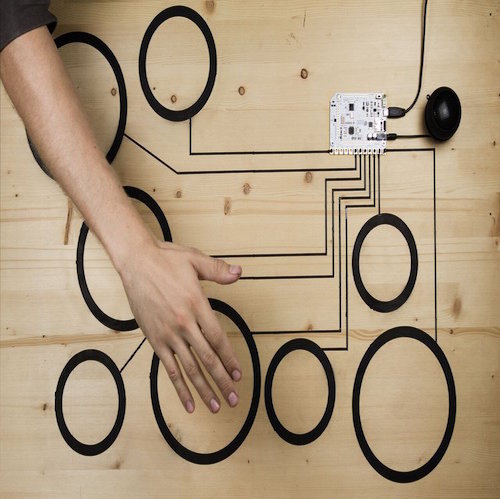

The first idea that I researched were patterns in traditional dance. In traditional Latvian dance, a very important component are the patterns created by the group of dancers. Every dancer has to be perfectly in sync with the others to create perfect lines, circles or other shapes as needed. I conducted further research into the Kinetic Art movement of the 1950s where sculptures depict a dancers movement over time in image. I also looked at more modern artists such as Heather Hansen [2], who creates intricate artworks in charcoal as a performance and Lesia Trubat González [3], who designed ballet slippers to track a dancer's movement. I realised this was not the direction I wanted to head in. The results would simply not convey my intentions clearly enough and it wouldn't be easy to source dancers for the project.

Another idea revolved around traditional choral music, but yet again there were too many issues and not a clear idea that I could focus on. Finally, I settled on the idea of "transliterating" dainas (traditional Latvian poetry) into images based on the daina:

Es satinu savas dziesmas I collected all my songs

Baltā diega kamolī; In a white ball of wool;

Kad aizgāju tautiņās, When I left my parents house,

Pa vienai ritinaju. One by one I sang them all.

The idea that songs, poems and stories can all be collected into one place so they are more easy to remember intrigued me. This also allowed for a combination of both the traditional backbone and a very rich visual language in the form of the symbols.

Dainas are short traditional poems usually following the trochee meter and less commonly the dactyl meter. The vast majority were noted down in the 19th century during the New Latvian movement [4], however, most [poems] are much older than that. The subjects range from everyday problems to important milestones of life, to deities and their role in the world. It is a folk saying that every Latvian has one daina that is his own. Dainas are also interpreted differently by different people. For some, they are a direct link to the past, an insight into the lives of ancient Latvians and their worries. For others, they are a source of inspiration for further works of art in music, painting, sculpture and more contemporary art practices. For others still, it is a memory of their homeland that they haven't seen in too long while for others still they are simply a boring part of literature they were forced to learn about in school.

The original "database" of dainas was created by K. Barons in the late 19th century. To aid in his work he had a special chest of drawers made, measuring 160cm x 66cm x 42cm. It contained 70 little drawers, each one further divided into twenty parts. Today the dainu skapis (chest of dainas) can be found in the National library of Latvia. And from 2001 the chest of dainas is a part of the UNESCO Memory of the World list. Today the process of collecting new poems hasn't stopped yet, a big problem is that it’s the older generation who have the largest amount of dainas and knowledge to impart and with their deaths the knowledge is disappearing as well. [5]

There are over 200 thousand poems in the online database and even more still not transcribed from handwriting to the website, and even more not yet published, hidden in the archives of the Latvian Culture Repository in the National Library. For this piece dainas to do with the sun were specifically chosen to mark the arrival of summer as well as celebrate Latvian centenary of independence. This focused the subject of the piece as well as lightened the amount of information that my database would need to handle.

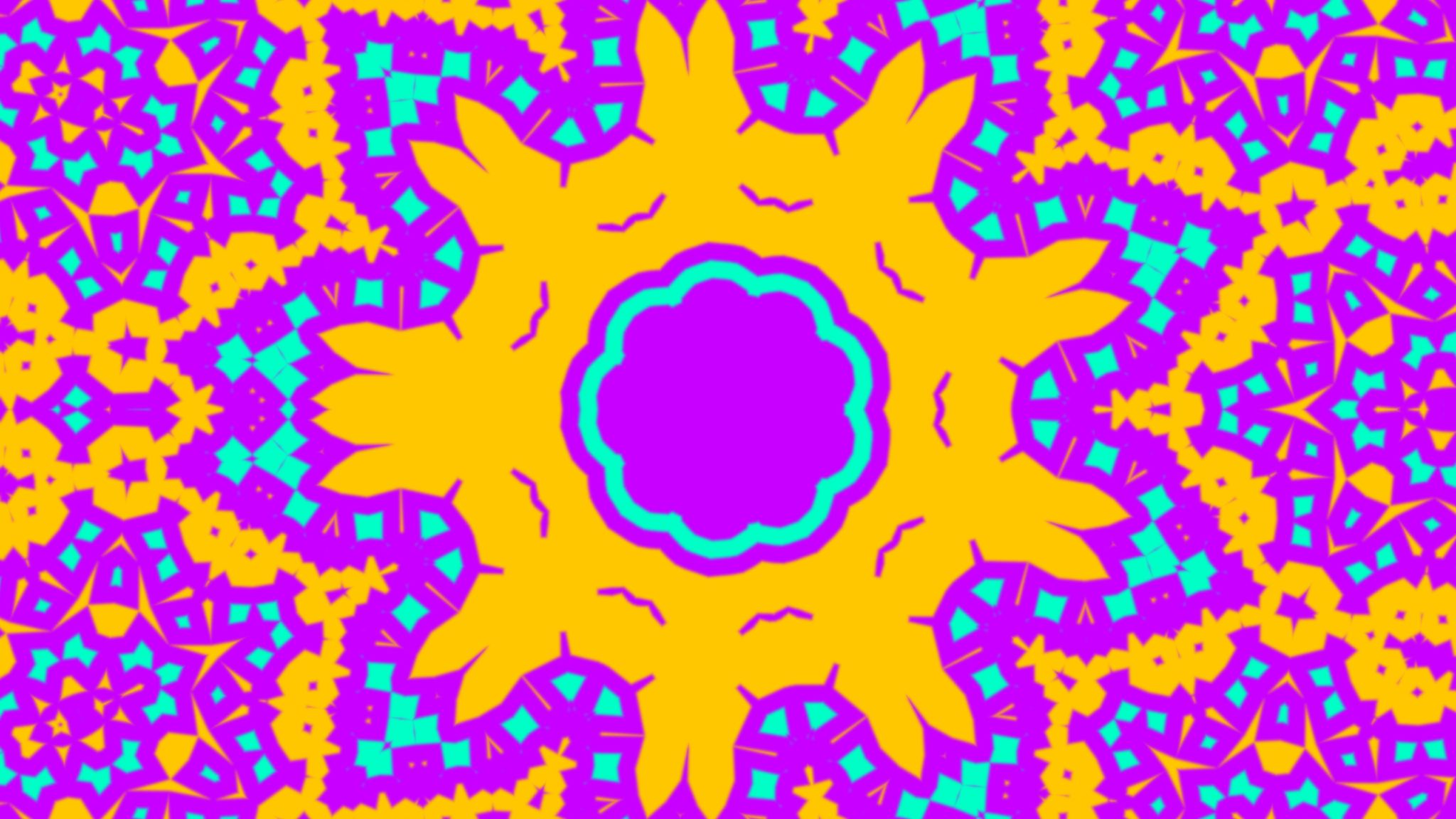

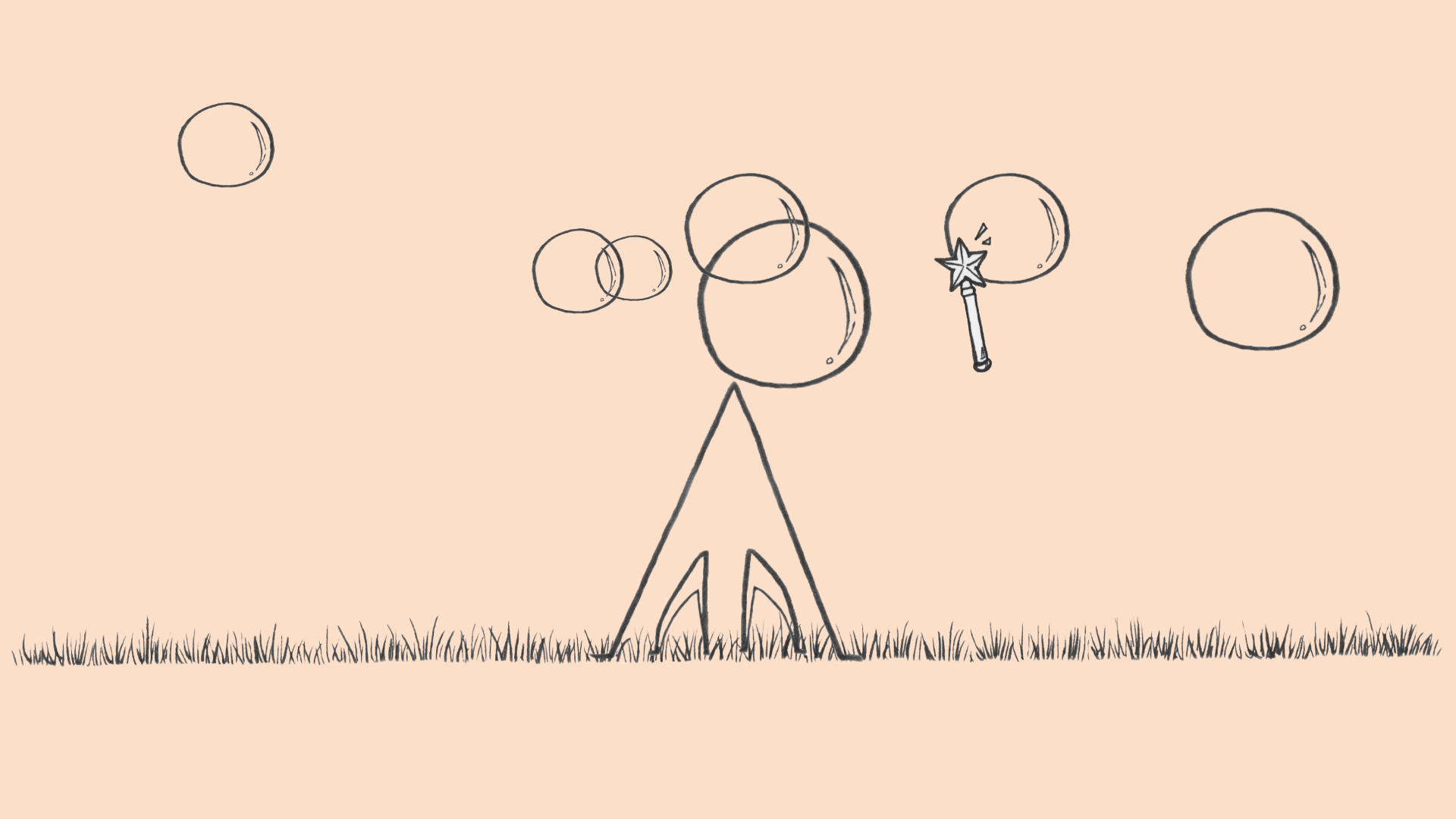

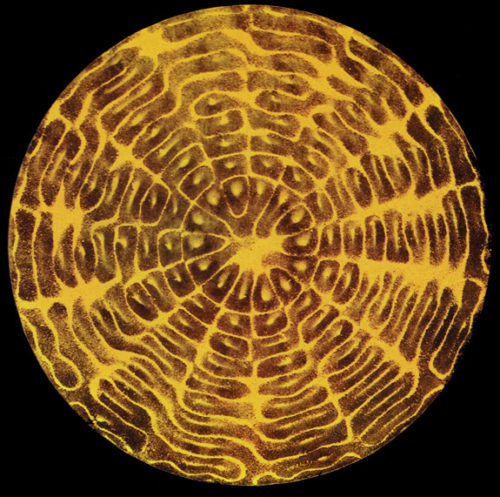

The symbols used in the making of the piece are also traditional and can be mainly found in belts mittens and other textile work. The words which already have a symbol associated with them (such as the Sun) received the symbol that “belongs” to them whilst other symbols were assigned at the discretion of the artist. The patterns themselves are traditional yet the finished result has been generated by a computer and therefore is removed from the original inspiration.

Latvian symbols are mainly found in textiles but there are also archaeological artefacts from the stone age where similar motifs can be found. Whilst most of the symbols have become an integral part of Latvian culture their names and meanings change drastically between different believers. V. Celms views symbols as containers of cosmic energies [6], others view them as simple ornaments to decorate objects whilst others yet believe they are a link with the deities and phenomena such symbols represent. For my piece, I choose to ignore a lot of the formal thought behind symbols and, rather than strictly defining that specific words get specific signs, assigned the symbols at my own discretion. It was important to me that the underlying symbols would be ones with meaning and that can be found in traditional arrangements of symbols. Other than that words which don't traditionally have a symbol but were repeated often enough in the poems received symbols with a similar idea behind the meaning.

An important part of my critical research was to conduct interviews with various different people and collect their opinions on both the subjects (where applicable). Most of the interviews took place in Latvia, however, people were also interviewed in Belgium and England. Overall I interviewed 13 people. Some of the interviews were informal and others did not feel comfortable speaking in front of the camera. I collected 7 filmed interviews.

My main objective was to gather opinion on what Latvians of different walks of life believed were dainas and symbols and what importance such things have on their life in their opinion. What was interesting was how many different issues and topics were raised by different people. D. Apsīte, for example, talked about only singing dainas from a certain period and with a certain moral code to them. The topics of dainas are so varied and all encompassing it is not difficult to find songs about drinking money away in a pub. E. Ikstena raised issues of banality and turning something with so much cultural value into a kitsch object for tourism. Signs and symbols, for example,

are currently very popular both with the locals and tourists. These are sold as scarves, bowties, phone cases, home decor and the list goes on. If the producer/artist of such objects isn't careful then the signs will slowly but surely lose their meaning. B. Reitzāne spoke of how common dainas and singing are to her homeplace and how people don't seem to attach much meaning to such things because they are so entrenched in it.

An interesting distinction could be seen when talking to people living outside of Latvia. Most hold on to symbols and dainas a lot more when not in their home country. It is no longer as commonplace nor as widely spread so people pay more attention to retaining the values. A large amount of information on the subject is also compiled by authors not residing in Latvia. People living abroad are more likely to wear traditional jewellery and know the meaning behind the signs. They have usually done more research on it themselves as well since information is not as widely available.

What came through in all the interviews was that almost everyone believed that these are certainly values to be protected and explored deeper. When asked if artists and designers should be allowed to create their own interpretations and variations the answers were a bit more varied, yet the opinion that as long as it is done with care and thought there is no issue with it emerged. As B. Reitzāne mentioned even the apparent mockeries of dainas written by bored schoolchildren aren't offensive because they know how to create it. They understand the linguistic structure beneath it and for the joke to work they have to know the original which they obviously do. Creating new variations is the only way tradition can live on.

Technical Research

The piece was coded in three main parts. The first part was a web-scraper which was coded in Python using urllib2, BeautifulSoup and Regex. BeautifulSoup allows for easy reading of Html whilst regex allowed me to get rid of the unnecessary Html elements. It also helped clean the poems up for inserting into the database.

The second part also consisted of Python using Pymongo and getpass to connect to the Mongo server. Rather than using localhost, I decided to host the database online so I would be able to access the database wherever I was working and so I wouldn’t be reliant on my machine but rather the server. Getpass was used to hide my credentials when signing in to the server rather than leaving an unprotected exposed string in my Python script. I also used mongo compass to visually, quickly and easily check exactly what the changes to the database were without having to print every document in the terminal.

The main issues in these two parts arose with Unicode encodings. Latvian uses Latin extended alphabet-a. While Python supports utf-8 encoding the problem is that not all web pages are correctly encoded and not all libraries are Unicode friendly. This meant that I had to be very careful in order to avoid my text from turning into illegible gibberish.

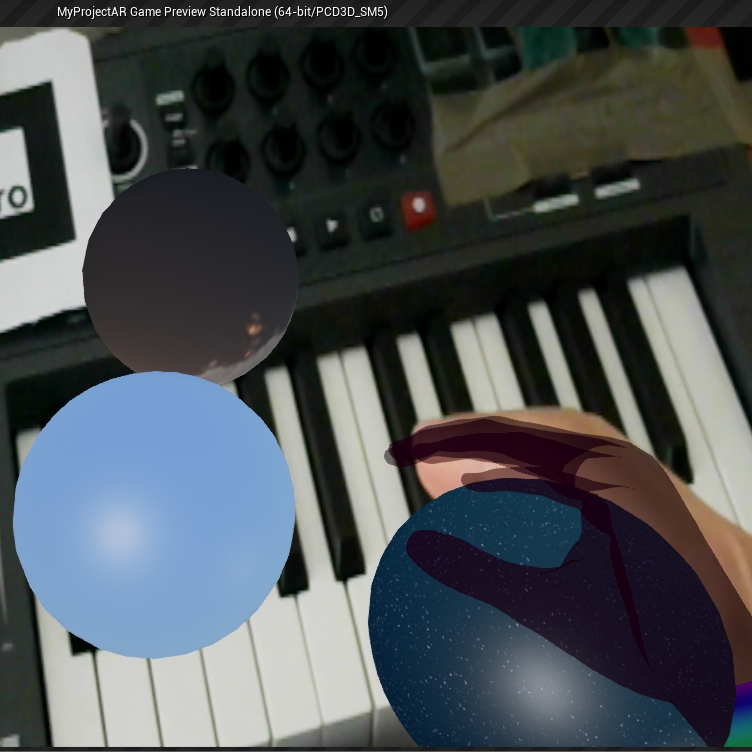

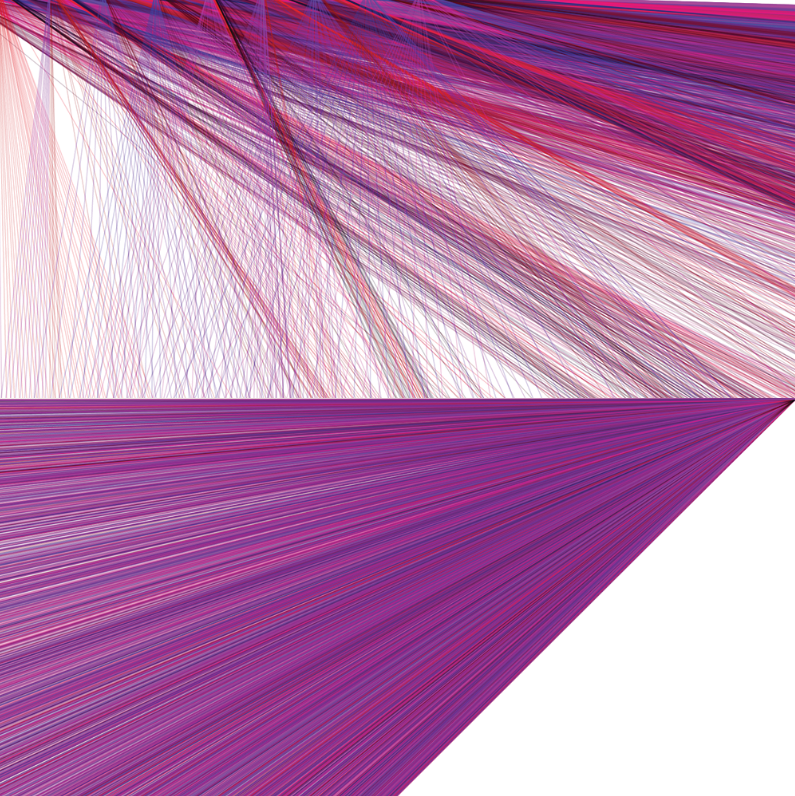

I created the main 20 signs which were assigned to the “main” words in Illustrator. It was important to me that the signs contain meaning and are representative of Latvian culture. These 20 images formed the basis for all other images used. Using Python and Image Slicer I subdivided the 20 images into 80 medium sized images. These medium images were further subdivided into 160 small images.

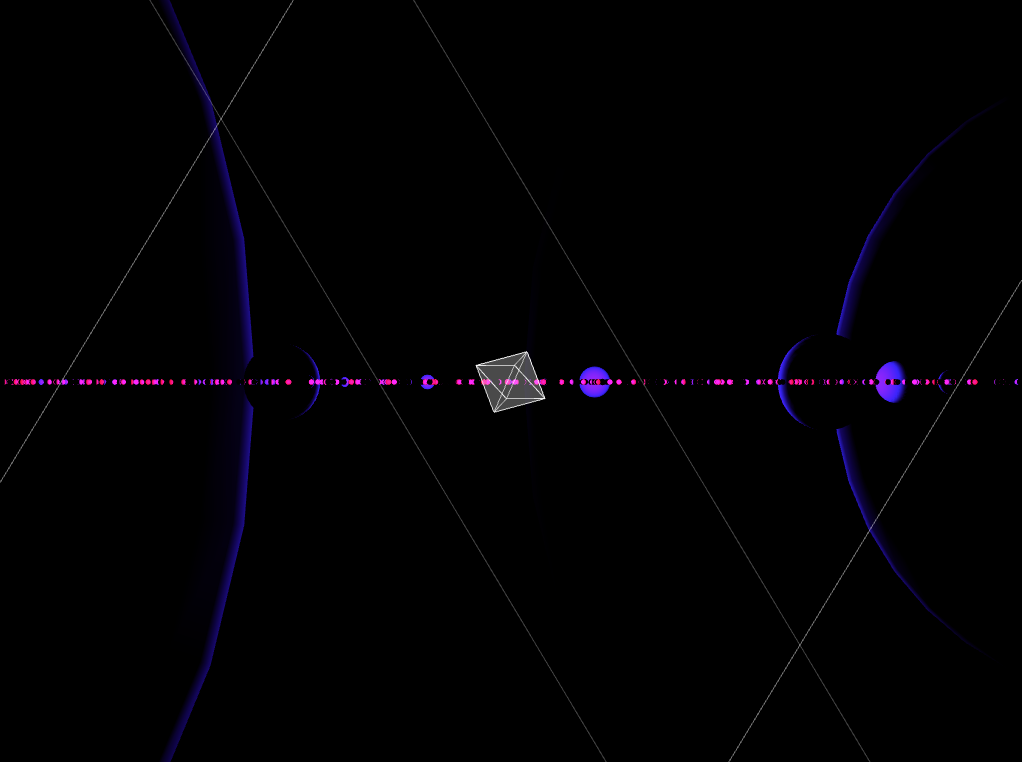

The third, and final, part of the code was written in Unity. Unity is very good for rapid iteration allowing for very quick tests of the code. It inherently has great sprite management that I used to my advantage when handling 260 images. Because it is mainly used for games programming getting high-quality screenshots of the render is also quick and easy to do. Unity is part of the C family that I was already familiar with from working with Processing and OpenFrameworks, yet it has a very large and very active community, which meant that debugging was easy and most issues were well documented.

To use MongoDB on Unity I used the driver created by the GitHub user rstam [7]. This part involved connecting to the database, getting a random daina and transliterating it into the image. First, my code created an array of words used in the poem that was then used to get the corresponding images from the word database. These images were then randomly placed in the document to create an image of the daina.

An important part of my technical research was also in the production of (what were originally intended to be) belts. The original intent was to have the belts produced as textiles. There were three main choices. Knitting on a knitting machine in the Goldsmiths textile department as last year, Embroidery on the new “fab lab” sewing machine or printing directly on cloth. All three were quickly dismissed as viable options. The textile department is very busy and hard to arrange for a time slot and the knitting machines are not very fast. The result would most likely be tapestries that I would need to cut and sew into belt shapes. Knitwear also looses shape very easily so I couldn’t just hang the belts as is. The embroidery machine seemed like a good choice, however, embroidery is also slow. Another massive issue was that the correct foot for the sewing machine was never found in the lab. The final idea of printing onto cloth was dismissed because it was simply too expensive for the end result.

The solution was the vinyl cutter in the new “fab lab”. Early tests showed that it can easily create the required patterns. However, the paper I used to carry out these vinyl cutter tests was lighter and much smaller. When it came to the actual production the cutter couldn’t be quite as detailed as I needed it to be. This forced a last minute change from belts to paper squares and a complete abandonment of belts with the poems. The machine didn't quite cut through the paper fully so each bit had to be removed by hand and with lettering, this task proved to be impossible.

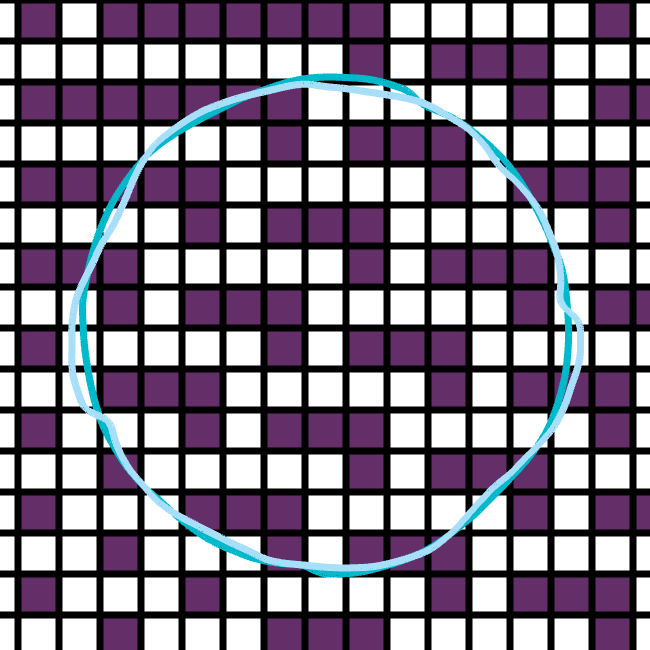

The frame was produced in plywood on the laser cutter in quarters of the final shape and screwed together. Then nails were hammered into the sides to allow for a fishing wire grid to be created from which the final transliterated dainas would hang. Fishing wire was chosen so that the final piece would look almost ephemeral.

Aesthetic Choices

The first and possibly most important aesthetic choice was the location of my work. Even though when we were first choosing our places in the gallery my final idea was fuzzy I knew my work would need space to "breathe". At that point, I was picturing a forest of textile belts, hanging from the sky, that the audience could wander through. This meant that the ceiling needed to be high so as not to create a claustrophobic feeling. I would also need to attach cables across the room which further shortened the list of possible spaces. There were only two choices that made sense to me- the tall room I had been in last year or beneath the stained glass window. It was decided that (almost) all the third years would be in the main space, but what was the last reason I choose to be beneath the stained glass was how well I thought the window would play with my piece. In my mind, mixing Christianity with the pagan symbols, I knew I would be using, was always an interesting prospect.

A lot of thought went into the fabrication of the poems and this went through a lot of iterations. They had to be lightweight so that the steel cables could support the weight and wouldn't fall down during the show. They would need to convey an almost traditional feel without actually being able to use the techniques Latvian symbols were originally produced in. The closest I felt was to create a textile piece again. There were several production choices, yet all the results would be time-consuming to make and relatively heavy. The other issue was the availability of the art departments textile labs. This led me to search for a different production method. Printing seemed too obvious and one dimensional but as the new "Fab lab" was opened I discovered that a vinyl-cutter was available and could be used to cut a number of different materials.

The final material chosen was white paper. Paper is light but strong. Paper also reinforces a link with written word. Perhaps an even more important reason,

personally, to use paper was that when I am not creating artwork with a digital touch I love creating handcrafted paper-cuts. The colour was chosen so the work would seem light and airy and almost ephemeral. Colour would have made it feel heavier and confused the audience. White also meant there was no need to figure out how to choose what poem is in what colour.

Unlike in my original designs where the poems would be free-falling from the ceiling, I quickly realised that I would need a frame to attach the poems to. This would work to my advantage in two different ways. A frame makes installing the work easier, as I couldn't imagine being allowed to go up high enough to attach each poem individually for health and safety reasons. With a frame, each poem can be attached beforehand and then only the frame needs to be lifted high. The second advantage was that the frame could very directly indicate what the piece is about. I choose to recreate the symbol for the sun since all the poems chosen have something to do with the sun, reinforcing the idea.

It was a conscious decision to use fishing wire to hang all the "poems" from the frame. It slightly gave them the appearance of floating in the air. An unexpected consequence was all the strings getting tangled during the setup. Fishing wire is notoriously hard to untangle as it is hard to see and very slippery and difficult to get a hold of the right piece. The untangling process was also complicated by the "poems" attached to it. There was a fear that pulling too hard on the wire would break the paper and the poem would then need to be reattached. This only happened to two "poems". The length of the fishing wire was also of importance so the piece would have a pleasing shape when it was hanging. I wanted the "poems" to almost reach the floor so the audience could explore them from closer and further away as they wished. The final shape of the piece was created on the floor using height measurements so the "poems" would hang at the right places.

On the floor beneath the piece, I placed the cut-outs from the frame hanging above. This is a simplified version of the sun. This, again, reinforces the idea that all the poems are linked with the sun. It also implies the idea of the different ways in which the sun can be perceived.

Divējāda Saule tek, A two-faced sun is in the sky,

Tek kalnā, tek lejā; Above the mountain and below;

Divējāds mans mūžiņš My life is double too

Ar to vienu dvēselīti. With a single soul.

The sun is the giver of life, but also the taker. The sun can be warm and gentle or it can be cold and hidden behind the clouds. The two varied symbols aim to showcase the many different ways the poems can be read and perceived in.

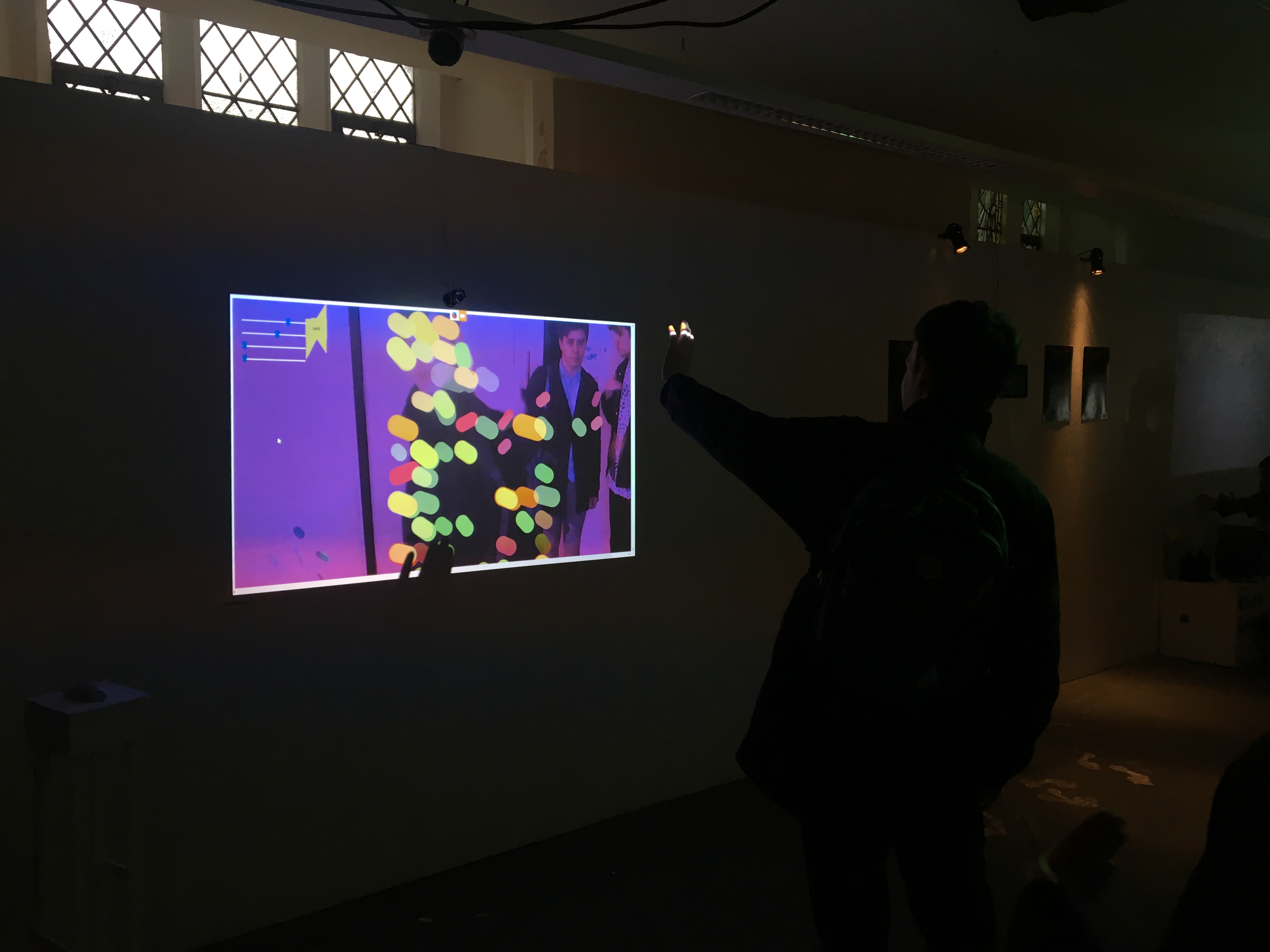

The final aesthetic choice was to put in screens. This was meant to serve as an alternative to a long write up explaining what the piece was about. Two screens were needed to keep a certain symmetry of the piece. The frame is so very geometrical that breaking the geometry and symmetry with badly placed screens would ruin the entire effort. The two screens also allowed for two different sets of information to be displayed. It was intended that one screen would display the translated "poems" whilst the other would show a video of Latvians explaining the significance and meaning of dainas and symbols to the general public. Sadly due to various technical reasons and time constraints the second video never happened.

Evaluation

Overall I am happy with how the project turned out. The idea evolved over time, yet that is to be expected. The main difference from what I had originally intended was that instead of having belts I had various sized squares. This occurred due to problems with the vinyl cutter. After the piece was produced the blade was changed. It had been completely eroded by the paper leaving a blunt stub instead of a sharp and pointy blade.

Another issue was that Latvian is very grammatically different from English. Words are conjugated depending on how they are used in a sentence. Nouns have seven different declensions which are then further dependent on 2 genders with 3 different ways of conjugating the word per gender. This meant that a lot of duplicates of the word were missed due to a lack of language parser. The only code I could find was a PhD thesis written in c++ that was beyond my knowledge level.

The audience response was similar to what I anticipated yet it wasn’t fully clear enough that each square was a transliterated daina. There are multiple ways of fixing this. One would be to (as originally intended) have the dainas also hanging and visible in the piece. Another possible solution was through the second video, where instead of every five images a daina appears, but the daina is next to the corresponding image. This wasn’t done because dainas are written in a very archaic form using words not often found in modern language. Some of the words are untranslatable to get the full meaning across. There simply wasn’t enough time to translate all the dainas that I was transliterating.

The non-Latvian part of the audience had a hard time understanding the background of the piece. This would have been solved by the second video. However, since the piece was originally intended for a Latvian audience I am not too disappointed with the results. My main intent wasn’t a political cause, to teach people about Latvia but produce a beautiful piece that would hold meaning for me. I believe I achieved that.

Some of the things I learned during the project include how to interview and film people, how text is encoded online and why it is such a headache, how to use a vinyl cutter and a laser cutter. I further developed my Unity and Python skills. My translation skills were also put to the test with the translations of the dainas. Perhaps, personally the most significant thing I learned, was how different this heritage is to the different people I spoke to. I have always seen it my Latvian heritage in a certain light and speaking to all these different people changed my perspective on what my heritage is, how to preserve it, continue creating it and honour it.

Github link

The final code has all been moved into a folder called Final.

https://github.com/debesmana/SignProject

References

[1] Alma Ulmane Portfolio http://almaulmane.com/latvian-patterns

[2] Heather Hansen http://www.heatherhansen.net/

[3] Lesia Trubat Gonzalez http://cargocollective.com/lesiatrubat/E-TRACES-memories-of-dance

[4] New Latvian movement https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Young_Latvians

[5] http://www.dainuskapis.lv/par-dainu-skapi

[6]Celms, Valdis. Latvju raksts un zīmes baltu pasaules modelis, uzbūve, tēli, simbolika. Rīga: Folkloras Informācijas Centrs, 2011. Print.

[7] rtsam https://github.com/mongodb/mongo-csharp-driver/releases